Community Mobility & Driving with Older Adults

Driving and Community Mobility* as an IADL

Community mobility is essential for people meet their daily needs such as going to the grocery store, the pharmacy, the bank and medical appointments. It is also essential for engaging with friends and family members whether they live a block, a mile, or a state away! People need socialize with others whether it be through clubs, religious organizations, community events, the gym or walking their dog.

In the United States, the primary mode of community mobility is driving, especially if you live in suburban or rural communities such as Greenville, North Carolina, the home of East Carolina University. As an occupational therapist, Dr. Anne Dickerson understands the importance of driving to the citizens of her city and state. Thus, she has been dedicated to studying driving and community mobility through research, collaboration with the ECU Health Medical Center, and teaching and mentoring occupational therapy students in this important “occupation.”

Driving and community mobility is considered an instrumental activity of daily living1 (IADL) by occupational therapy practitioners. Since addressing activities and daily living (ADL) and IADL are the mainstays of occupational therapy practice, occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants should understand and address driving and community mobility issues with their clients.1

Relationship to Occupational Therapy

Driving and community mobility is considered an instrumental activity of daily living [1] (IADL) by occupational therapy practitioners. Since addressing activities and daily living (ADL) and IADL are the mainstays of occupational therapy practice [2], occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants should understand, and address driving and community mobility issues with their clients.

Community mobility is essential for people meet their daily needs such as going to the grocery store, pharmacy, bank, and medical and/or other appointments.

Community mobility is also essential for engaging with friends and family members, whether they live a block, a mile, or a state away.

We have learned that virtual time is good, but not enough; we need to spend face to face time with the important people in our lives. Individuals also need socialize with others on a regular basis whether it be through clubs, religious organizations, community events, the gym or walking their dog.

*Reference: Doucet BM. Quantifying function: status critical. Am J Occup Ther 2014;68(2):123-6 doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.010991 [published Online First: 2014/03/04].

Understanding Driving Behaviors

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) are everyday tasks, such as shopping, cooking, managing your finances or medication and driving. However, driving is one of the most complex IADL, not because it is harder, but because it is done within a highly dynamic environment.

While cooking can be complicated, if a person with dementia becomes confused while cooking, they may burn the food or forget to add an important ingredient, without causing harm to anyone else. When a person with dementia gets confused while driving a vehicle, the potential risk of injury goes beyond the driver.

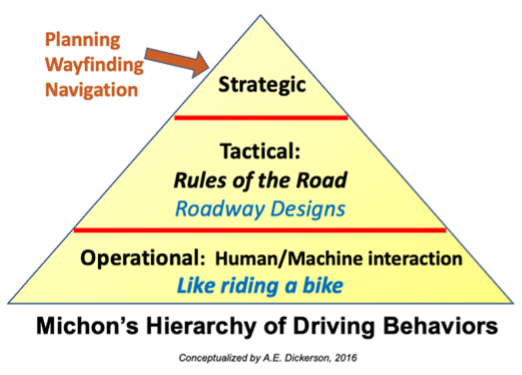

Operational level is the overlearned human-machine maneuvers necessary to control the vehicle (e.g., using the brake, turning the steering wheel). These are the overlearned skills of “motor memory;” driving is indeed “like riding a bike.” It is why it is difficult to tell someone with dementia they cannot drive, because if fact, they can operationally. The truth is they are not fit to drive because of the disease process

Tactical level is related to decisions made while driving. Examples include slowing down for rain or potholes, stopping for a yellow light, making a turn, and deciding which lane to use. These decisions are governed by traffic rules and also tend to be overlearned and practiced habits. Moreover, updated roadway designs have improved safety such as protected left turns, arrows painted on lanes, channeling of lanes. These design changes have made it easier and safer for all drivers, as fewer critical decisions are necessary with such embedded protections.

Strategic level consists of decisions about the mode of travel (e.g., vehicle, walking, biking), the goal of a trip, and how to get to a destination. However, even with the best of planning, there are wayfinding and navigational issues one may need to do on any excursion. For example, when a construction crew blocks a usual roadway, the driver must recognize the situation and negotiate another route. These unexpected occurrences are often why older adults with cognitive impairment get lost in familiar areas. While physically able to drive and respond to basic road rules, their capacity to problem solve in changing and dynamic situation is significantly impaired.

Thus, when an older adult is informed about a medical condition that may impact his or her driving ability, it is important to discuss driving with a primary care provider and/or family member. Other important information and solutions can be found at Plan for the Road Ahead, a website designed for older adults and families to plan for driving transitions and planning.